12th to 14th February 2020

Please Note: Videos covering the material in this blog post can be found at the bottom of the post.

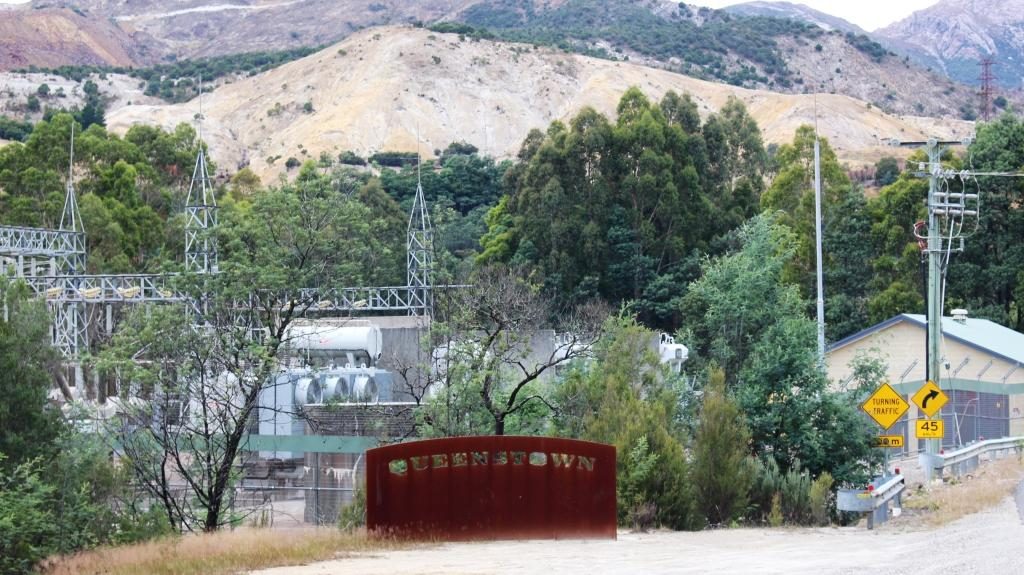

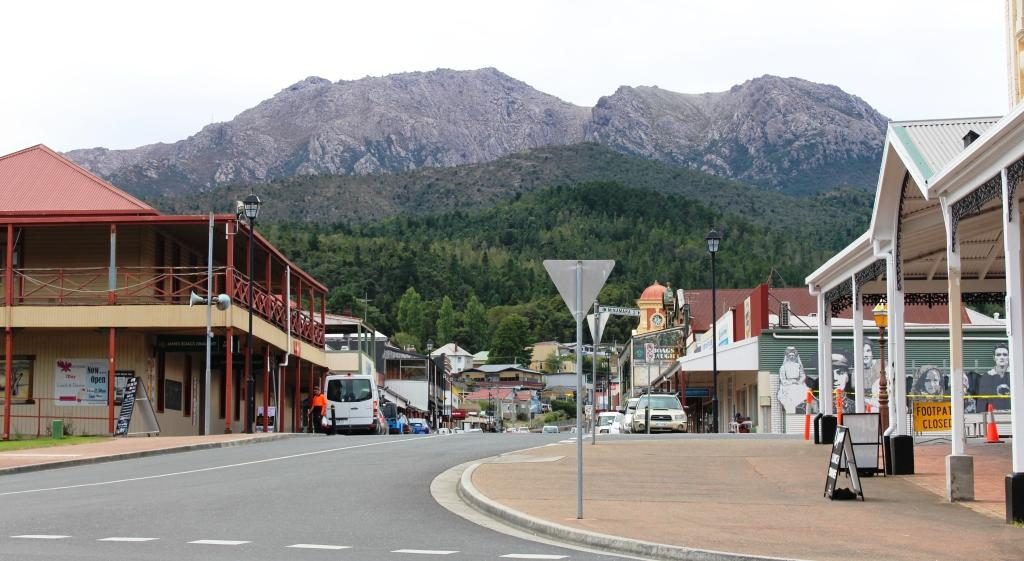

There was a suspicion of drizzle as we packed the car to leave Strahan. In several areas, as we drove to Queenstown, our way was partly obscured by cloud cover that sat atop the mountains like a blanket. The point from which we viewed the mountains behind Queenstown the previous morning was a totally clouded, with no view at all. As we approached Queenstown, banks of cloud hung in front of the mountain range, but all of the cloud vanished as we drove up the range towards the east to give us an almost cloudless sky.

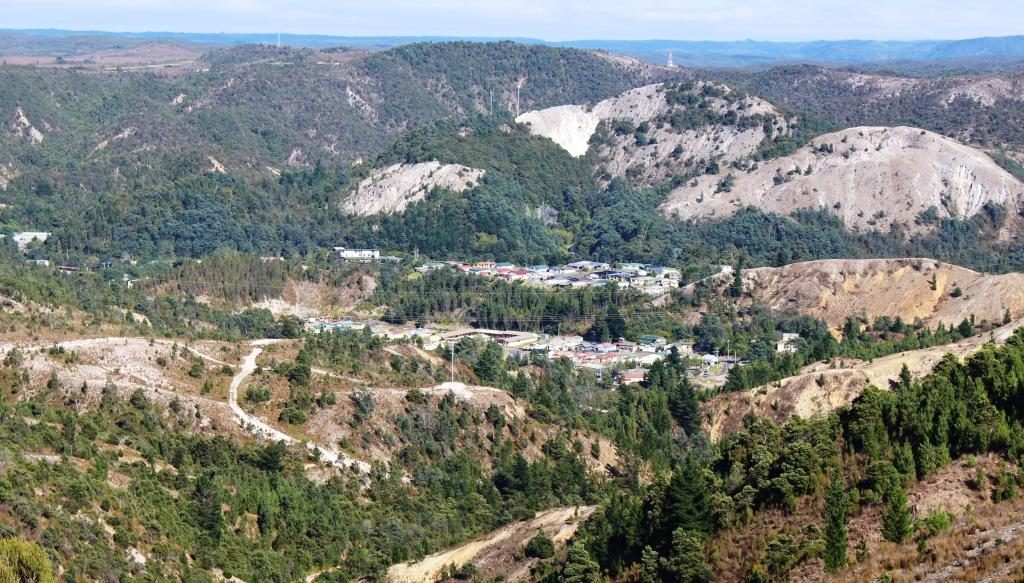

We paused at Queenstown for fuel and stopped again at the observation point part way up the baron slopes for that final view of the town.

Lake Burberry is one of Tasmania’s newer dams. The Lyell Highway crosses it by bridge at its narrowest point. A National Parks camping area on the east bank provides picnic facilities, so we stopped there for morning coffee.

The road from the dam to Derwent Bridge runs through endless national park, and is lined with an infinite variety of vegetation as it passes over mountain ranges and through rain forest filled valleys.

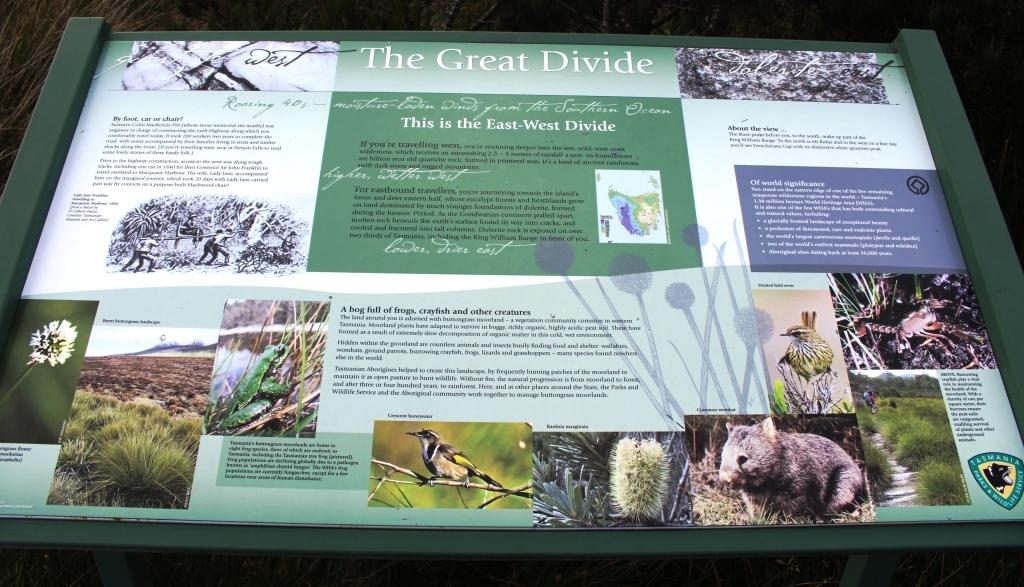

At a number of places along this road there are parking areas giving access to short to medium walks to features such as lookouts and waterfalls. One parking area is the starting point for longer walks that extend to several days in the area of the Frenchman’s Cap range. Another stop marks the highest point in the range that divides east from west. Interestingly, we could see Frenchman’s Cap from the boat on Macquarie Harbour. At 1,446 metres it is quite prominent.

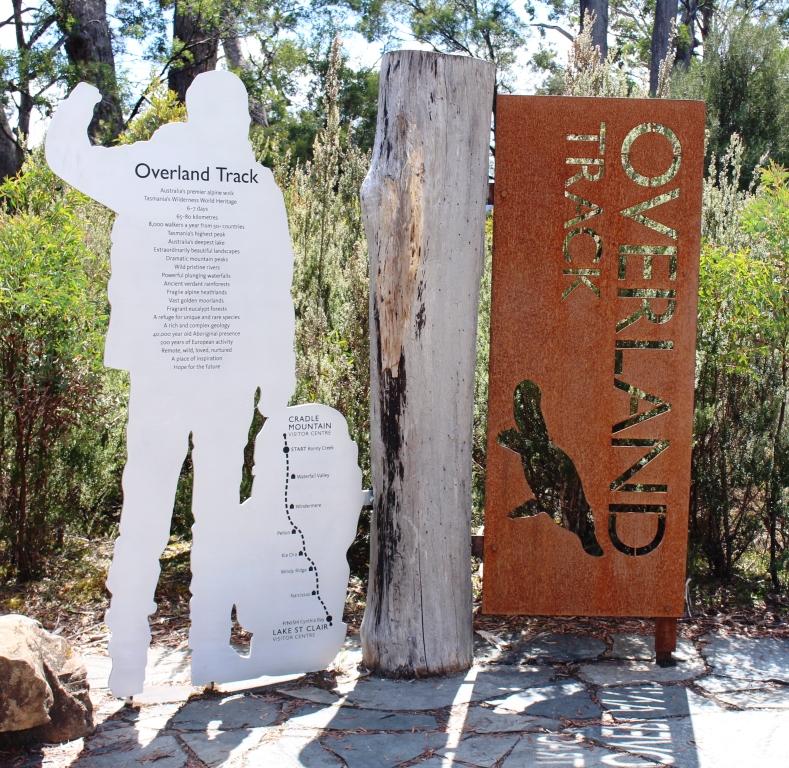

We turned at the small town of Derwent Bridge for the short drive to the Lake St Clair National Park Visitor Centre. As well as being a worthwhile place to call, it is the southern end of the Cradle Mountain to Lake St Clair 6 to 7 day walk. Many hikers, carrying back packs, were either arriving from the walk or waiting to leave to walk north. A ferry service links the southern end of the walk with the visitor centre at Lake St Clair.

We had intended to have a picnic lunch at Lake St Clair, but we were attacked by a swarm of March flies. Tasmania seems to have a March fly plague but today was the worst that we had encountered. So the picnic went back in the car and we took refuge in the restaurant.

It is about 140 km from Derwent Bridge, mostly down the Derwent Valley, to New Norfolk. Most of the journey is through mountainous timbered country. The road passes a number of dams used for hydro electricity generation. In the Tarraleah area, we saw a couple of sets of huge water supply pipes descending steeply into power stations.

The forests finally give way to farm country with grazing cattle beside the road. Just before New Norfolk, orchards appear along the banks of the Derwent, which is quite a substantial river at this point.

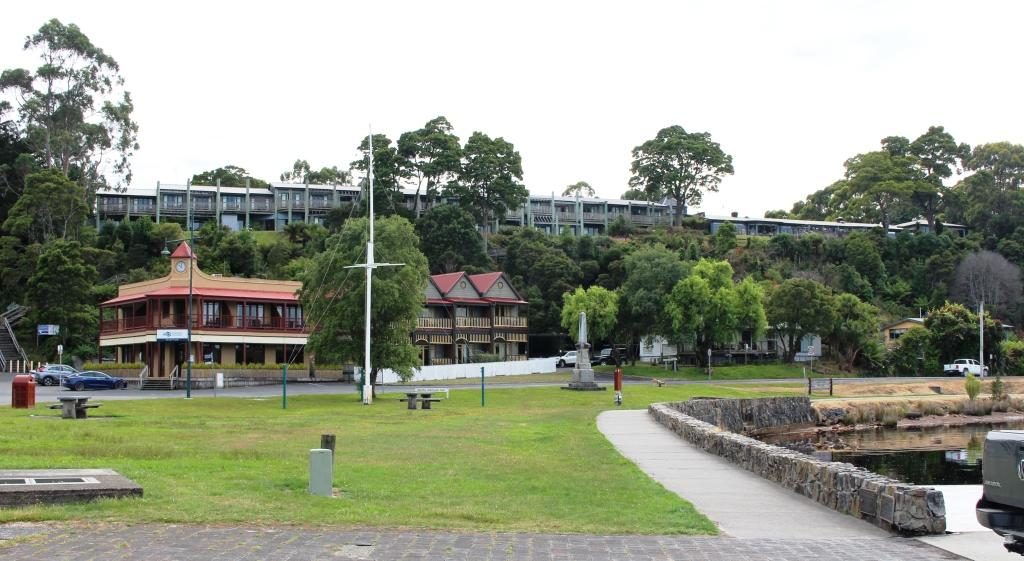

Our apartment was on a hillside overlooking the Derwent River, with views over the town on the eastern bank and the mountains beyond. We were there for three nights. New Norfolk was our first encounter with a digital reception. A sign on the door gave a phone number to call, A code was then sent, by text message. The code was our door key.

If someone tells you that more trees should be planted, tell them to visit Tasmania. We spent yet another day driving through trees, trees and more trees. Tasmania’s south and south west have an abundance of trees.

We started the day with some medical maintenance at a New Norfolk pharmacy and then headed for the trees and the mountains. In Tasmania trees and mountains seem to go together.

The road on the west side of the Derwent is a shorter route to Mount Field National Park. There is quite a lot to do in this extensive park but time limited us to the short walk to Russell Falls. Like many falls walks the path leads along the ravine that carry the waters of the host stream. The view of the tiered cascade is all the reward needed for the easy 30 minute walk.

Like Lake St Clair, the visitor centre here was busy. There are a number of walks and other attractions and it is only about 80 km from Hobart. Some walks lead to elevations that provide views back along the Derwent Valley to Hobart. Given an absence of cloud, of course.

We then drove on a further 95 km along the Gordon River Road to reach the Gordon Dam and Lake Gordon. It is a lonely road passing through a handful of small locations, the last and most substantial of which is Maydena, followed by 70 km of sealed mountain forest road.

Lake Gordon and its neighbour, the better known Lake Pedder, are just over a ridge from each other at Strathgordon. There was a huge environmental fight over Lake Pedder that the Hydro Commission eventually won, which helped achieve its icon status.

Strathgordon was only ever a dam construction town. Nothing much has changed, with administration and some worker accommodation still there. What was, I think, the single worker facility, is now a wilderness lodge that provides accommodation as well as the facilities of a pub, cafe, restaurant and coffee shop. Fuel is available as well.

These huge water storages look fantastic as they lie among the mountain ranges, some of which are densely forested and others massive piles of almost bare rock. A clear sky produced striking reflected blue water.

The dam that holds back the waters of Lake Gordon is quite a sight at 140 metres high with a pronounced curve in the wall to cope with extreme pressure. Both lakes cover more than 500 square kilometres and hold the equivalent of 37 Sydney harbours.

Gordon and Pedder dams are connected by a narrow channel that carries water from Lake Pedder to Lake Gordon. Lake Pedder appears not to have its own hydro power generator. Its water is directed through the Lake Gordon.

The return journey is over the same road as we travelled outward bound. We used Maydena as an ice-cream stop, pleasantly absorbing the warmth of the afternoon sun as we enjoyed the treats. And so, back to our comfortable unit, which was easily the best accommodation that we had so far occupied in Tasmania.

The next day, Friday, dawned overcast with a chill breeze. Just the day to drive through areas where snow regularly falls during winter. We were bound for The Great Lake in the Central Highlands of Tasmania but by an indirect route.

We drove down the east bank of the Derwent River to Bridgewater and joined Highway One, heading north. Downstream from New Norfolk, the river is not as confined by its banks and sprawls into wider expenses of water, some of which are shallow and marshy. The bridge at Bridgewater is at one this wider area so the bridge is rather long with a causeway and a lift section for taller boats.

Highway One, the Midland Highway is the main road link between Launceston and Hobart. After about 50 km we turned left for Bothwell, a small rural town, full of historical buildings. A sheltered corner in the park provided a morning coffee stop and a pause while we looked at history dating back to early settlement in Tasmania. The area was settled by farmers in the 1820s.

After Bothwell, the road continues to the North West until Miena is reached. Miena is a spread out town of highland holiday houses and well housed permanent residents. A couple of small hills provide lots of water view opportunities over the southern end of the Great Lake.

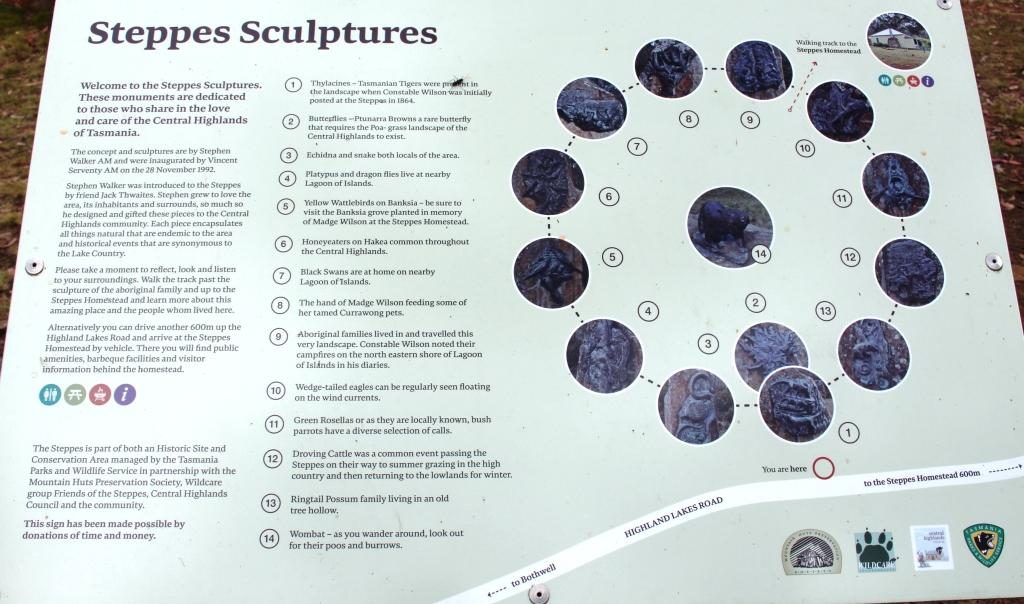

The only real point of interest along the road to Miena, about half way, is a collection of sculptures, in the bush just off the road. They are at the end of a short dirt road with a small parking area. The road is marked by a simple sign that announces the “Steppes Sculptures”.

A short walk away a circle of twelve stone plinths each hold a bronze sculpture with a thirteenth in the centre. They are the work of Stephen Walker, a well known sculpture who has work that decorates the Hobart waterfront and who sculpted the whale memorial at Cockle Creek. More of Cockle Creek in a future post.

The area is known as The Steppes, presumably because it is part of the area that “steps” up to the highlands. A historic farm house on the property can be visited either by a short walk or a short drive. We passed up on the house as it is not often open and it was not a day to be out of the car for too long without being rugged up.

Just before Miena we pulled off the road to look at the Miena Rockfill Dam the construction of which created The Great Lake by backing up the Shannon River and caused two smaller lakes to become one much larger lake. A lookout provides excellent views of the retaining wall and the lake that backs up to the north, way out of sight. On the south side of the lake is Shannon Lagoon. But more of that shortly.

We drove further into this very spread out town and found the Central Highlands Lodge, a sort of guesthouse hotel of the kind that you find in these kinds of places. We were served a good hot meal suitable for the day and, of course, coffee. We then drove on through the town and along the road to the west of the lake that would have taken us to the Bass Highway, but the clouds were below the tops of the distant mountains and showers of rain were moving over the surrounding planes and across the lake. Frankly, it was quite uninviting, so we turned around and headed back into town.

When I was learning about Mount Bischoff tin and Mount Lyell copper at school I was also learning about the Tasmanian hydro electric generation industry and particularly Tarraleah and Waddamana. I remembered Tarraleah because we had spent a night there 45 years ago and it had snowed. We had driven through this town two days before and noted its steeply sloping water pipes feeding the generators. But where was Waddamana? That question was answered on the drive earlier in the day when we had seen a sign pointing to Waddamana and the historic hydro electric trail. The turn was about 15 km back towards Bothwell.

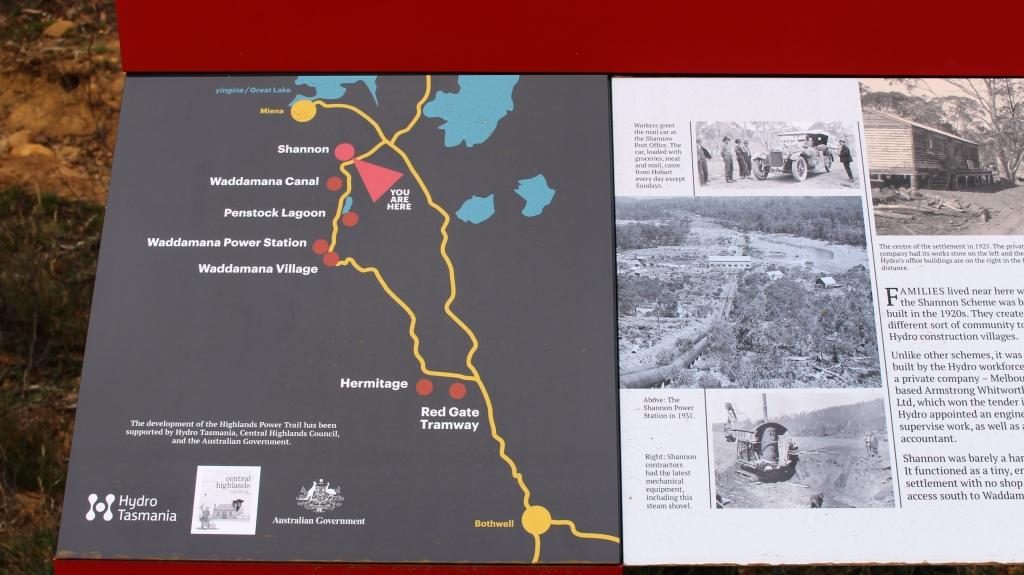

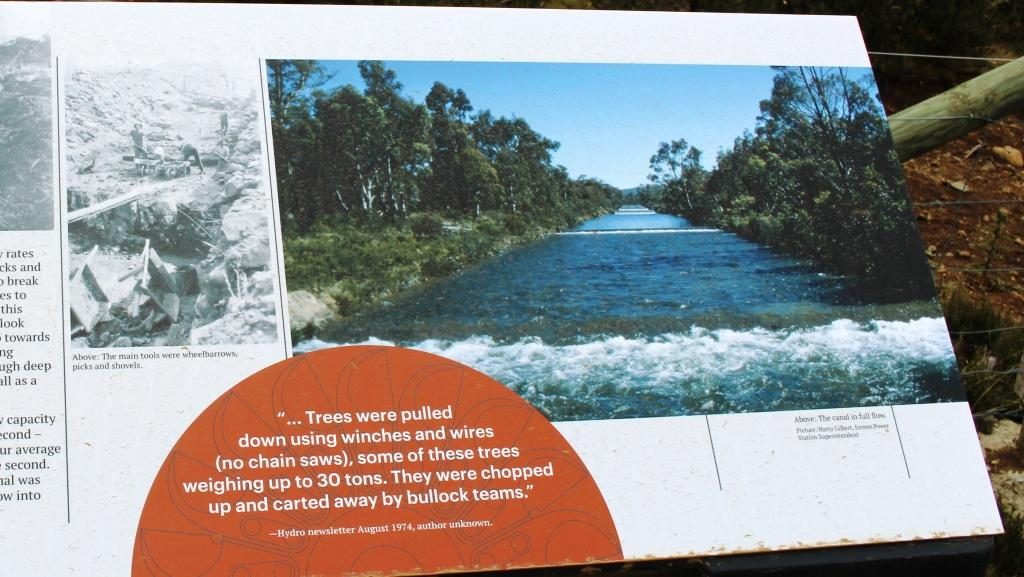

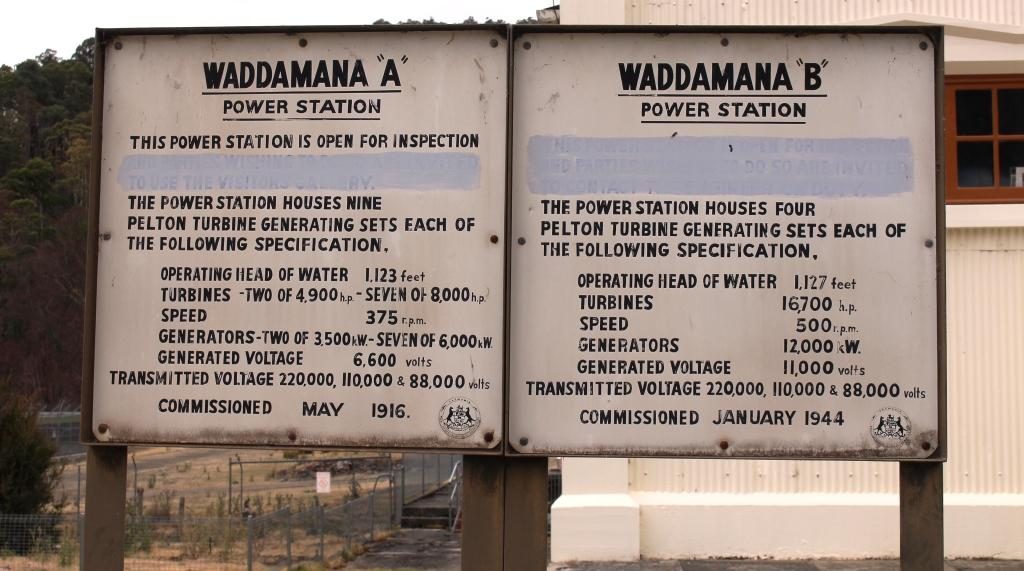

The great lake is the birthplace of serious hydro electricity generation in Australia. It all started in about 1910 when a dam was built at the bottom of The Great Lake which channelled water through pondages and canals to the top of a steep slope and shot it down the slope to Waddamana A power station. The scheme was commissioned in 1916, held up by bad weather and the start of WWI.

Shannon Lagoon was a balancing pondage which fed water into a manmade channel that carried water to Penstock Lagoon. From this temporary storage water was released into another man made channel and then down the precipitous mountain side to Waddamana A. There was a construction town named Shannon but it ceased to exist many years ago.

Waddamana B was commissioned 1946 so was slowed, in its turn, by WWII. This expansion of generation capacity greatly increased the output of Waddamana and helped to set the paten for future power generation.

Waddamana A is now a museum with most of its turbines still in place with some cut away to show what really makes the system work. I was able to walk through among the equipment and gained a good understanding of it. Most of the pipes that fed water to the turbines are still in place although truncated and often incomplete.

There was a small town at Waddamana back then which is still there but not used for power station workers any more. Some of the houses appeared to be occupied. On a hill above the town and power station a new and substantial wind farm has been built. The wind vanes were still against the afternoon sky but we heard on the news a few days later that is had been officially commissioned and was in production.

We made our way home on an alternative road that was sealed so long ago that it was like driving on gravel but it was in surprisingly good condition. It brought us back to the Lyell Highway at the town of Ouse which is on the Ouse River, a tributary of the Derwent. The final part of our drive was again through the vinyards, orchards and hop fields of the Derwent Valley.